100 Years

100 Stories

It was 1940 when my great-grandfather moved into this house. Dwarkadas Jamnadas, his fashionable wife Motibai, his widowed sister-in-law, and his eight sons. The ninth was born here. Every inch of this house, right down to the floors, was done up in Bombay Deco.

Bha, as he was known, had 15 grandchildren, and 18 great-grandchildren. Most of the family has lived in this house at one point or another. Some, naturally, had to move away – Calcutta, Bangalore, Los Angeles. But Marine Drive is still home.

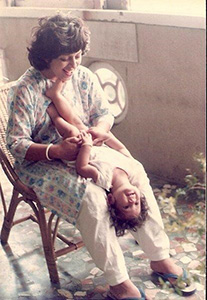

I’m the oldest of the Bombay cousins, and grew up here. My cousin Avantika, a year younger, was brought to nani’s house every weekend. The two of us didn’t need adults around to entertain us. We didn’t want them. We had each other and our secret games. I think she will forgive me for revealing them to the world now – ‘Come Here/No’, ‘Spaceship’, ‘Dinner’s Choice’.

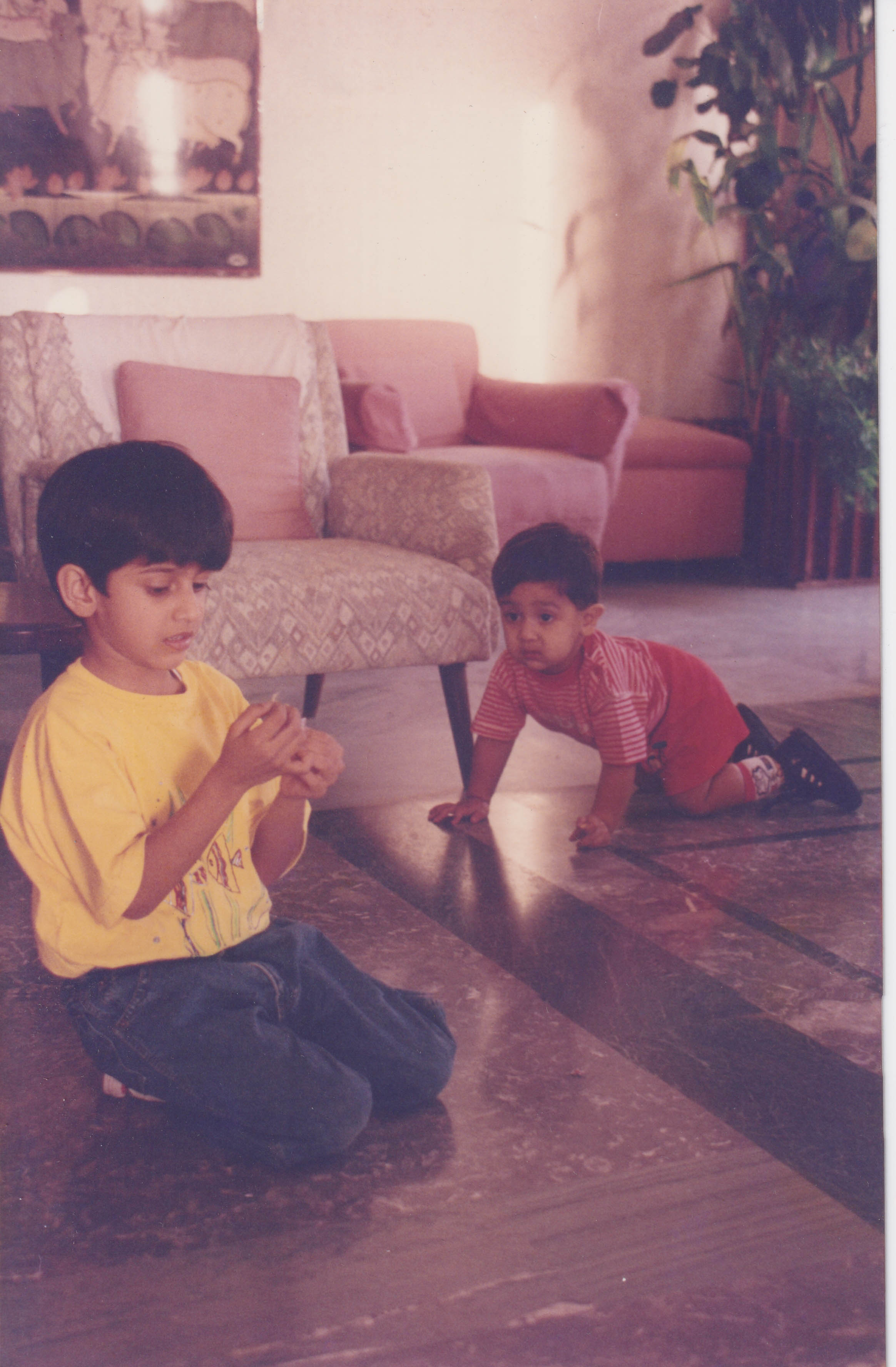

We were rudely interrupted by the birth of younger siblings and cousins. Our parents demanded that our ‘spaceship’ have enough space for everyone. We were forced to turn meticulously planned games meant for two into games for ten. We progressed to catch-and-cook, land-and-water, chor-police and a variety of other games to keep the peace. And in these, our floors played an important part. Eclectic and beautiful, the common areas are a light grey marble with white, and have lines of green running through them. These areas are large, open spaces, with plenty of room to run around as our parents sipped their evening chai. Our parents themselves had used these floors as natural hopscotch grounds, and their lines as cricket boundaries. We have never grown up in a house where the elders told you not to play indoors. It was encouraged; a blessing in a city that lacks open spaces.

To make the games more difficult as we grew up, we would move to the small alcove just off the airy living room, and lock ourselves in. The tiles changed. Green, orange, and white terrazzo in a 15x15 room. Ten kids. One ‘denner’. Step on the orange, and you were safe, step on the green, and you were fair game. No falling, no whining, and shoo your parents away if they came to get you. This was our space. No one else was allowed in.

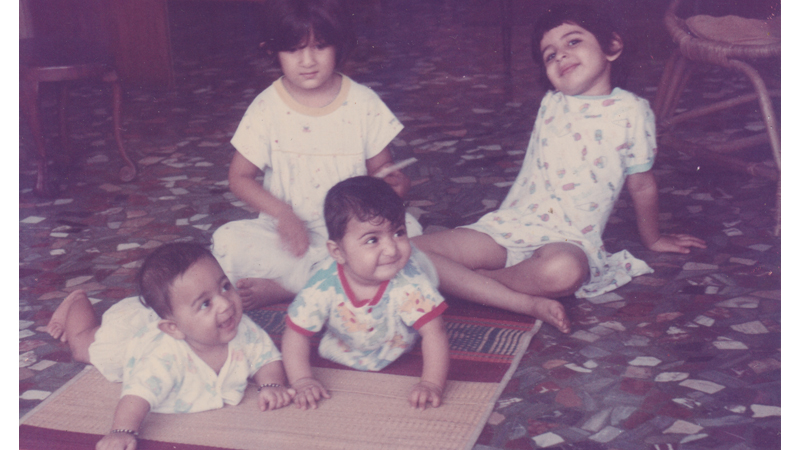

With 18 cousins though, there were always babies around. Our games were too dangerous for them. Just off the alcove is an enclosed terrace. Its floor is made up of tessellated tiles on a deep green background; leftover fragments of those used all over the rest of the house. This floor helped. Put the babies on their bellies and the colours provided them hours of entertainment!

I never really thought about how much of a part our floors played in our childhood. We took them for granted. But it turns out you don’t need a Playstation to keep yourself entertained if you have a Bharat Floor. They’re still there in that old house, completely unchanged, waiting to be secret-keepers for the next generation of cousins.

You may also like

-

09Deco GlitzSee for yourself the most chic art deco flooring schemes created by Bharat, which were all the rage in the Bombay design circles of the 1930s! Who knows, you may be inspired too?!Read More

09Deco GlitzSee for yourself the most chic art deco flooring schemes created by Bharat, which were all the rage in the Bombay design circles of the 1930s! Who knows, you may be inspired too?!Read More -

10ColourexA versatile offering, Bharat's Colourex was a brand new material that adorned the facades of many Bombay buildings! From creating retro inspired murals to replicating the look of the Malad stone, Colourex could do anything.Read More

10ColourexA versatile offering, Bharat's Colourex was a brand new material that adorned the facades of many Bombay buildings! From creating retro inspired murals to replicating the look of the Malad stone, Colourex could do anything.Read More -

12Those who walked on a Bharat FloorA former US president? The King of Pop? A cricketing legend?! See our list of whos been walking on Bharat's floor!Read More

12Those who walked on a Bharat FloorA former US president? The King of Pop? A cricketing legend?! See our list of whos been walking on Bharat's floor!Read More