100 Years

100 Stories

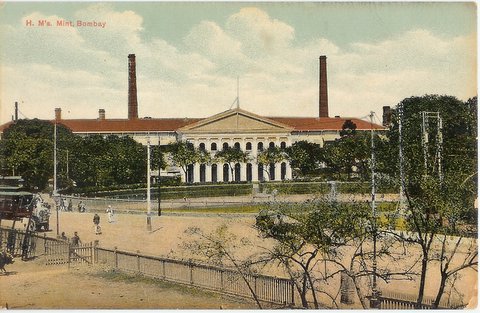

The Royal Mint. Gonsalves, Jose M. (fl. 1826--c. 1842), Lithograph, coloured, 1833, British Library. As per a Testimonial Booklet published in 1940, renovations made to the Royal Mint, Bombay in the 1920s/30s is listed as one of the jobs done by Bharat Tile and Marble Co.

U.S Franz, of the Public Works Department, had seen Bharat’s tiles in many public and private buildings. Their “excellent quality and superior finish” had greatly impressed him. When he took over his post as the Chief Engineer and Joint Secretary to the Bombay Government in the mid-1920s, Franz made sure that Bharat’s products were installed in as many buildings under his control as possible.

Until only a decade ago, this was most unusual. While British colonial architecture had started adopting local materials, encaustic tiles for floors were predominantly imported from Europe. Agents dotting presidency towns imported crates of single colored clay tiles in regular geometric shapes and combined them to form the most exquisite Victorian flooring schemes. The Rajabai Clock Tower, the Royal Bombay Yacht Club, the Bombay High Court and the grand Victoria Memorial in Kolkata became emblems of power, designed to endorse imperial authority.

With the introduction of Bharat’s 8” X 8” carpet pattern tiles the tiling industry was irrevocably revolutionised. The Bharat tile was substantially cheaper, continually available and far quicker to lay. As the company diversified into a range of indoor and outdoor tiles, and imported and synthetic marbles the Bharat floor became the preferred choice for several imperialist structures.

Here, we take a look at three such structures that symbolised the colonial era: the Governor’s House - the seat of political power; the Railways, masked as a public service, that helped the British gain control of a vast hinterland and the Breach Candy Club - a secluded haven by the sea, away from prying native eyes. In each of these structures, the resoundingly swadeshi Bharat Tiles and Marble Co. received much appreciation for the work done.

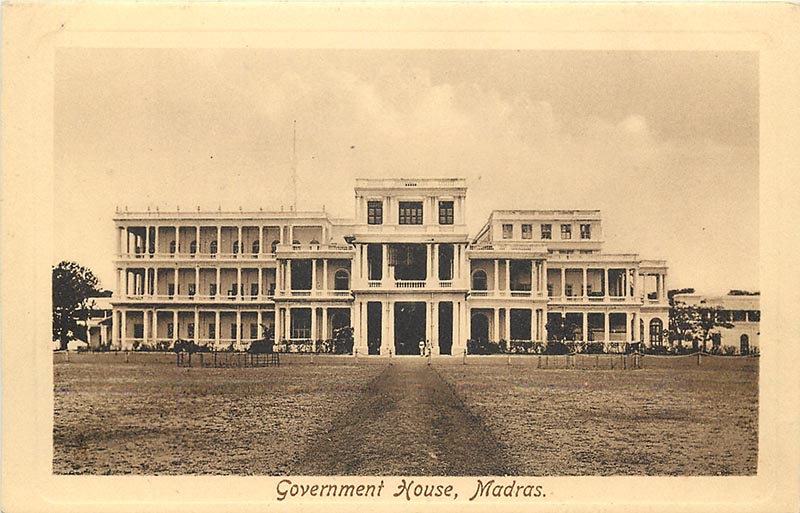

Governor House, Bombay, Pune and Madras

For the British, India was once the land of Maharajas and Durbars. The English bureaucrats in India were conscious of demonstrating a similar imperial character of their rule and a Government House symbolized this thinking. A Governor had not just status but the paraphernalia that went with it comprising the A.D.C.s, Secretaries, Body Guards, the Band, a troop of servants, stables of coaches and horses and authority over vast territory. The Governor’s residence and office went together and public functions such as banquets and balls saw close to 200 invitees. And then there were the public audience – the durbars where entire retinues are located on the complex around the Government House. Though 19th century structures, these Government Houses were periodically refurbished and expanded to accommodate royal visits and evolving functions of the Governor’s Council. It is no mean feat for the Bharat Tiles and Marble Co. that as early as the 1930s, its products – presumably, marble and plain cement tiles, added to the sheen and elegance of a magisterial life.

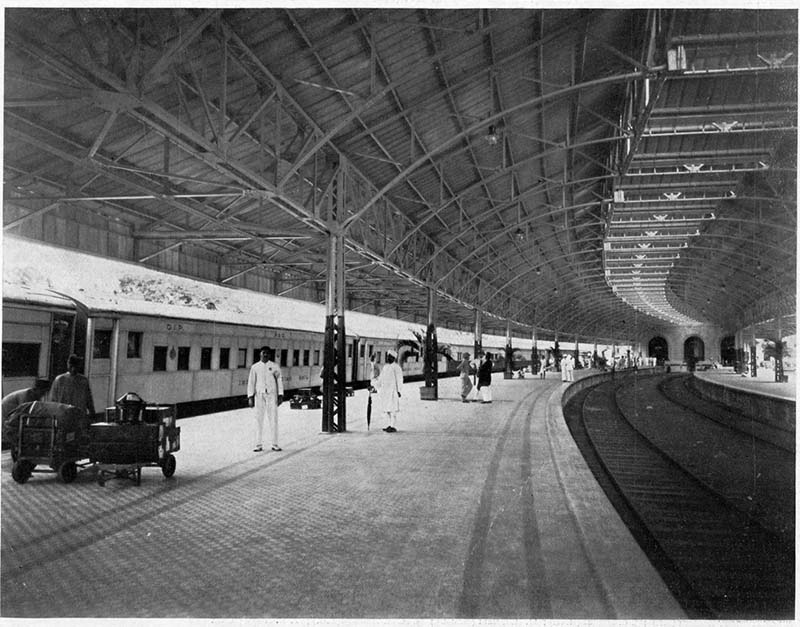

Ballard Pier Station

Few are aware of the erstwhile Ballard Pier Mole railway station on the Port Trust land within the Ballard Estate precinct. But even fewer are aware that almost 40,000 sq.ft. of Bharat tiles were used at this site and proved to be a great validation for the company’s almost fanatic obsession with quality and durability.

So close to the docks, the Ballard Pier station, which operated between 1900s and 1944, was a hugely popular stop on the G.I.P Railway network and provided a direct link for Europeans disembarking at the docks and heading to mofussil towns. Some of the oldest trains in the country - The Punjab Mail and the Frontier Express ran from this station all the way to Peshawar.

The platforms of the erstwhile Ballard Pier railway station, were paved with cement tiles of a special non-slip chequer variety. It was “grey in colour picked out with green bands and black borders”. J.A Rolfe, the Deputy Chief Engineer of the Bombay Port Trust in a paper delivered before the Bombay Engineering Congress in 1933 reveals his apprehension regarding these tiles - “It was thought that the light grey might in a short time be spoiled with ‘betel nut juice’, but exhaustive tests on sample tiles indicated that the surface of the tiles was so dense that the stain would not penetrate.” But his fears were allayed for even after 12 months of installation, “there was no sign of staining”. The platforms were washed every morning and this removed any dried up juice without leaving any mark.

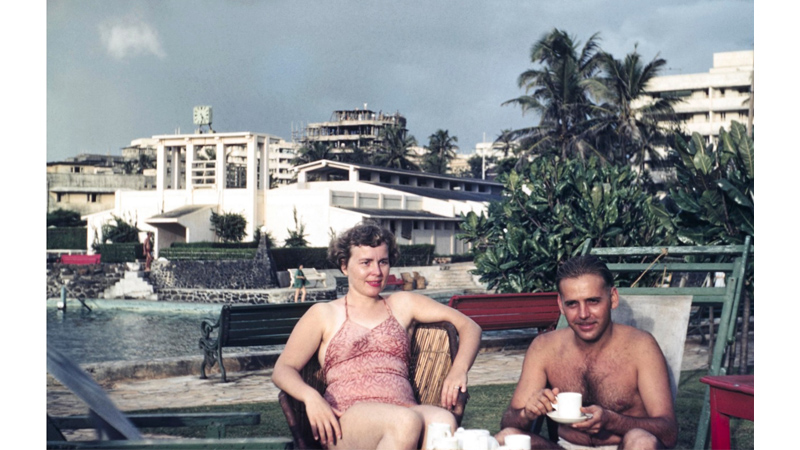

The Breach Candy Swimming Club

“In building the pool during the Raj, the British were emphasizing their ownership of India, their iron control over its borders and its topography.” - Samanth Subramanian

This is by no means an over-exaggerated statement. The pool of the Breach Candy Bath, where a young Salman Rushdie could spot only “pink people cavorting”, was exclusively for the European public - residents and visitors - of Bombay and was indeed built in the shape of colonial India, with a center platform placed where Delhi would be on a map.

The original baths having fallen into disrepair, proposals for reconstructions were initiated in 1925 which culminated in the new baths from funds subscribed by the European community. While the intent was certainly discriminatory, the structure ironically was built using Indian materials. The Indian Concrete Journal of November 1927 notes that the flooring of the surround and the various rooms were all carried out in cement tiles supplied and fit by the Bharat Flooring Tile Company of Bombay. Again, one sees the company’s special non-slip chequered tile gracing the pool-side of the club.

As per company records, Bharat supplied its products for several British structures from the era such as University buildings, bungalows and residences meant for bureaucrats, hospitals and clubs. “In all cases,” states Franz in his letter written in 1932, “they have given perfect satisfaction in terms of durability and freedom from bulging. They compete very favourably with tiles manufactured in foreign countries and are also very economical.”

You may also like

-

08BFT Classics: 1930s Madras UniversityBeating competition to win this coveted contract, Bharat executed a splendid mqarble mosaic and terrazzo work in the Madras University. This temple of learning was one of Bharat's most proud projects.Read More

08BFT Classics: 1930s Madras UniversityBeating competition to win this coveted contract, Bharat executed a splendid mqarble mosaic and terrazzo work in the Madras University. This temple of learning was one of Bharat's most proud projects.Read More -

09Deco GlitzSee for yourself the most chic art deco flooring schemes created by Bharat, which were all the rage in the Bombay design circles of the 1930s! Who knows, you may be inspired too?!Read More

09Deco GlitzSee for yourself the most chic art deco flooring schemes created by Bharat, which were all the rage in the Bombay design circles of the 1930s! Who knows, you may be inspired too?!Read More -

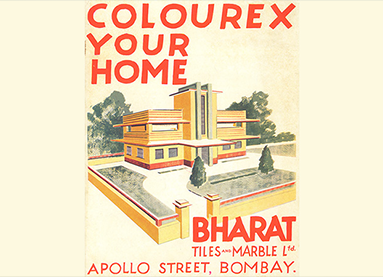

10ColorexA versatile offering, Bharat's Colourex was a brand new material that adorned the facades of many Bombay buildings! From creating retro inspired murals to replicating the look of the Malad stone, Colourex could do anything.Read More

10ColorexA versatile offering, Bharat's Colourex was a brand new material that adorned the facades of many Bombay buildings! From creating retro inspired murals to replicating the look of the Malad stone, Colourex could do anything.Read More