100 Years

100 Stories

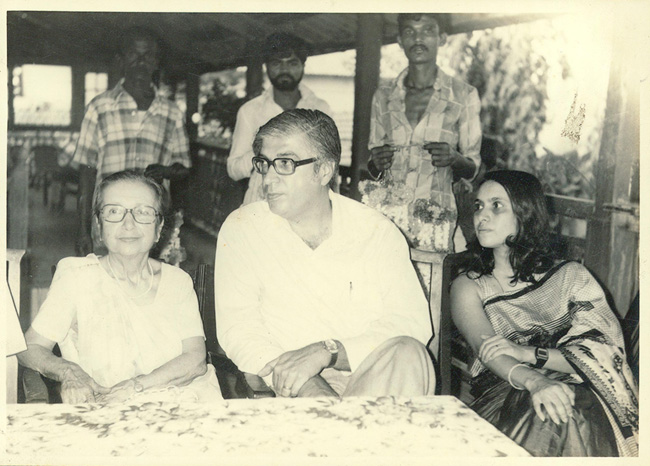

Dilnavaz Variava née Sidhwa’s warmth and vivacity has won many hearts over the years. She is the brand’s most enthusiastic ambassador and a sentimental custodian of its envious legacy. For the archiving team charged with researching the history of the company, at every turn of the journey our search began and ended at her office. Tucked away at the very end of BFT’s office, Mrs. Variava has a cupboard packed with files, leaflets and photographs handed down to her by her parents or collected by her. Always generous with her time and insights, hours spent with her revealed not only her unwavering passion for her products, but the trials and tribulations which epitomize the instinct for survival that entrepreneurs have to summon to keep their legacy, and their business, relevant.

Born in 1944 in a joint family in Mumbai, Dilnavaz literally grew up with the iconic Bharat Floors. Dina Building, a home constructed for the extended family by her eldest uncle and named after his wife, had every floor tiled with Bharat tiles. “Whatever was left over at the factory was put into the building and every two rooms would have a different pattern!”. The 12-seater table in the dining room would groan under the pressure of every breakfast, lunch and dinner. The annual pickle and ‘patrel’ making sessions would have the large kitchen filled with all the ladies cooking, and chasing out a gaggle of children trying to swipe things before they were ready. Mrs Variava laughs as she recalls that “It was a huge joint family where we had a lot of fun because if there was a birthday or Pateti or whatever, one went around to all uncles, aunts and elderly cousins and said, “It’s my birthday today!” and collected something from everybody by way of a gift.”

Women across the Indian Subcontinent were predominantly uneducated and usually managed the home. However, the Sidhwa ladies were no ordinary ladies. Dosibai, Dilnavaz’s grandmother, was the glue that held the family together and kept the family’s liquor business running even after her husband died and until the British rulers closed down all local liquor distilleries. For Dilnavaz, her grandmother was a remarkably modern woman. “She insisted that she wanted to get into an aeroplane and fly over Bombay, which she did through one of those joy rides. And she took all the maids to see a movie, “Bathing Beauty” after she saw and liked it! She kept the whole family together. I mean the fact that all the brothers liked to go together with their families for holidays meant that she had really created good feelings and bonding within the family.” My mother also helped my father with Bharat Tiles when he fell ill and started the warehousing business when the company made losses in the tiles business. The men in the family were supportive of women getting an education and working. The grit and pragmatism of these ladies had a lasting influence on Dilnavaz.

Contrary to the orthodox traditions in those days, it was never assumed by her parents that girls needed to marry at an early age; rather, education was prioritized. Dilnavaz’s parents pushed their two daughters into acquiring an education that would enable them to run businesses. “My father made no distinction about whether you were a boy or a girl; he wanted us to be bold and not to feel limited in any way, and not be intimidated by gender or status”. Due to her father Pherozesha’s failing health, which made spending half his time in a dry climate a necessity, Dilnavaz studied in Deolali until class two before shifting to Pune, when her older sister Almitra got admitted to one of Pune’s premier colleges. Mrs. Variava would like to think that she was not a good student “ I would much rather play and I didn’t think it was a good idea to study. But my mother used to harass me to study and I would feel very discontented about it”. But the ‘nagging’ proved to be successful, for Mrs Variava stood first in Pune in her senior Cambridge, with A’s in all her languages. Neither Dilnavaz nor her sister, Almitra, wanted to be in the business. Dilnavaz had to study Commerce, rather than liberal arts, due to her father’s insistence. “He always said that both of us needed to know how to run the business because there was no son”. She applied and got admission to Wharton, LSE and IIM Ahmedabad, but chose IIMA rather than study abroad, with corporate funding and a bond as the family had financial stress at the time. She says , “ I wanted to be very independent with my life and I did not want to be under a bond with anybody.”

One of the first two women to graduate from the newly established Indian Institute of Management, Dilnavaz found the business education useful but what she valued was not necessarily materialistic but more driven by social causes. In fact in a study of values of MBA students, she was told that her score had to be omitted because it was so high on philosophical values and so low on economic values that it was distorting the class scores ! “From 1973 onwards I was able to focus on social causes and issues, rather than just on a career in business, which would not have been satisfying for me”

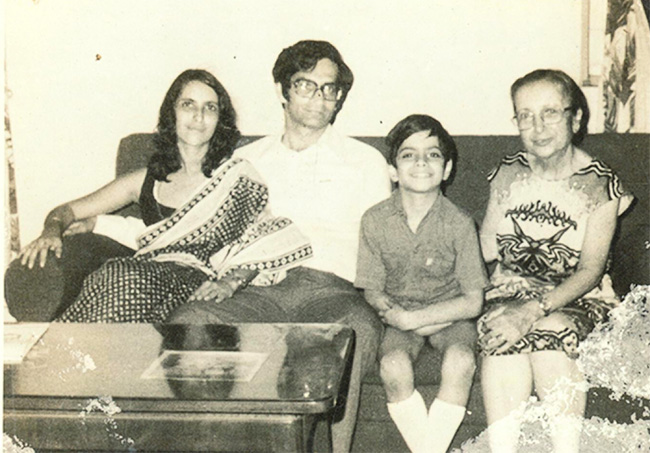

Driven, intelligent and creative, her ideals combined with her management skills and business knowledge, guided her through various transitions in her life. She started as an executive at Voltas, and from there she went on to work on a project with Norton International in USA and then as Personnel and Admin Director of Grindwell Norton Ltd. She resigned in 1973, when her son was born, to work as a part time CEO of World Wildlife Fund India (WWF-I), while simultaneously being a non-executive Director of Grindwell. Finally, it was with her joining Bharat in the late 1970s, that the company got a fresh lease of life.

From the 1960s till the 1980s, Bharat suffered significant losses with the emergence of multi-storey buildings and the builders’ desire for cheaper tiles, rather than quality tiles. Some large clients also caused large losses by not paying sums that were due to the company. Dilnavaz, after she saw her mother cutting short her vacations for business reasons, realised that the company was going through a rough patch. She resigned from WWF, but continued working honorarily for environment conservation as Vice President of the BNHS and on apex Government of India committees. After she joined Bharat Tiles in 1978 she played a crucial role in settling the large outstandings to offset the losses incurred by Bharat over the years. She then took over the handling of Bharat’s warehousing business. By dealing with issues fairly, in keeping with her principle to find win-win solutions, she was able to develop good relations even with those with whom the company had disputes.

To Dilnavaz, “ When a seed is planted, how it is tended matters. When it sprouts, how it sprouts, who benefits from the fruit are unknown, but all the little things that are done, they all have their impacts and that's why I'm writing chronicles now for the children and grandchildren. This message should go on from generation to generation, that you do not live only for yourself, you live for your family and society and your country and the world. The concept of Trusteeship is not just for personal enjoyment, but it is something which we should use for bettering the lives of those less fortunate than us”.

As far as second chances go, the year 1999 was a watershed moment for Bharat and Dilnavaz. It was at this juncture that she could have shut the tile business and sold it off, retiring altogether. Facing 30 years of losses, all the other shareholders wished to sell off the company or liquidate its assets. However, the prospect of selling the tile business did not sit well with Dilnavaz, though she agreed to the wishes of the other branches of the family. Bharat was the legacy of Pherozesha, Rustomji and Tehmina Sidhwa, built with their toil and creativity, and Bharat Tiles had been the gold standard of cement tiles in India for over 75 years.

Serendipitously, one day, entrusted with clearing the factories and warehouses at Kurla before the premises were sold, Dilnavaz came across some beautifully designed objects in brass that she had never seen before. It made her wonder what they were. Curious, she inquired about these "beautiful brass things" and discovered that they were stencils and that they were originally used to make carpet pattern tiles in the 1920s before being discontinued in the 1940s. They lay unused, collecting dust for fifty years before she came across them. Dilnavaz saw in them a way to restore the floor art that she had seen in her own home, Dina Building, and in many iconic buildings in the city. Equally serendipitously she discovered the company’s earliest design catalogue which gave the colour combinations of the tiles made from the stencils. She instinctively saw an opportunity to revive the company and save the jobs of those who would otherwise have to be laid off.

In 1999, for the first time, the Kala Ghoda Association had decided to hold an art and heritage festival in the Kala Ghoda area of South Mumbai. It took place in the same neighbourhood where the Bombay Natural History Society office was located. They approached the BNHS to join the Committee to identify the trees in this heritage precinct. Dilnavaz was requested to represent the BNHS. In the course of Committee discussions she realised that the focus of heritage restoration was largely on the facades of buildings. Dismayed by the replacement of Bharat’s artistic floors with unimaginative marble and ceramic floors, her intention was to encourage architects and designers to preserve such floors in heritage buildings. “I suggested that I would try and create an exhibition about what the flooring used to be like. I was delighted that the Committee agreed to it, but the problem was to relearn our own lost design heritage.”

Dilnavaz researched and sought out people who could help to recreate the original carpet pattern tiles. She says, “The exhibition finally consisted of the history of floorings of the past century, including China mosaic, and how the different types and designs of floorings evolved over the decades. And how our cement tiles evolved too.” The response to their exhibits spread across the garden of the David Sassoon Library was overwhelmingly positive. It was crowded with visitors who recorded their delight and their nostalgic recollections of these floors…as did the crows in the surrounding trees ! These tiles also drew the attention of architects and interior designers interested in sensitive restoration. Their support contributed to building Bharat’s name in the Heritage Restoration scene.

When interest in these Bharat tiles began to pour in following the exhibition, Dilnavaz Variava, infused with entrepreneurial drive, chose to take a chance with Bharat as opposed to closing it down. But her decision was fraught with uncertainty.

It was at this point she asked herself why she should revive Bharat. “On one hand, I remember my sister saying to me, why are you taking this on? You are going to put a millstone around your son’s neck!” Re-establishing Bharat from its current situation would be a challenge but, on the other hand, Dilnavaz had three reasons for doing so.

“Firstly, why should workers and staff loose their jobs because management had not been able to make the business profitable, if there was now a chance of doing so? Secondly, Bharat’s tiles had been the benchmark for quality in cement tiles, and closing the company would destroy that. Finally, the company was the legacy of Bharat’s founders and, if possible, she should pass it on to her son, Firdaus and let him decide whether he wished to keep the business alive.

Dilnavaz took a chance, a daring chance, to chase a newfound dream. She recalls “For me, the highest principle was that if I can turn it around - which I felt I had a good chance of doing- I should do so. Once I saw the old stencils and the excitement that people had, I felt this was possible. There was a risk, but something was there. Something new that could make a difference to the company. I called the three seniormost managers – heading Finance, Production and Sales- and asked them whether they would prefer to take a good financial settlement and work elsewhere, as they were young enough to do so, or take a chance on turning the company around. I asked them this question on three occasions and each time they chose to take the chance on turning the company around! The other shareholders too were supportive of my decision, so I went ahead”.

The bet did pay off. Bharat picked up its first project for the revived Heritage range tiles from the Rugby Hotel in Matheran. And the rest is history.

You may also like

-

48Archival Find: Business CardCurious about how inquires for businesses carried out before the era of smartphones and Google? Presenting to you Bharat's collection of business cards from the 1990s till dateRead More

48Archival Find: Business CardCurious about how inquires for businesses carried out before the era of smartphones and Google? Presenting to you Bharat's collection of business cards from the 1990s till dateRead More -

49My Home Series: Aarti Parasrampuria, Brady's Flat, ColabaHigh ceilings, heritage tiles and an apartment that evokes a visceral feeling of admiration - Aarti Parasrampuria's home in Bombay's iconic Brady's apartment in Colaba remains a vintage dream come true for the modern day entrepreneurRead More

49My Home Series: Aarti Parasrampuria, Brady's Flat, ColabaHigh ceilings, heritage tiles and an apartment that evokes a visceral feeling of admiration - Aarti Parasrampuria's home in Bombay's iconic Brady's apartment in Colaba remains a vintage dream come true for the modern day entrepreneurRead More -

50Many Hued EvolutionRed, blue, retro pink or sombre greys - trace through how the colours offered by Bharat played an important role in visualising and shaping a place.Read More