100 Years

100 Stories

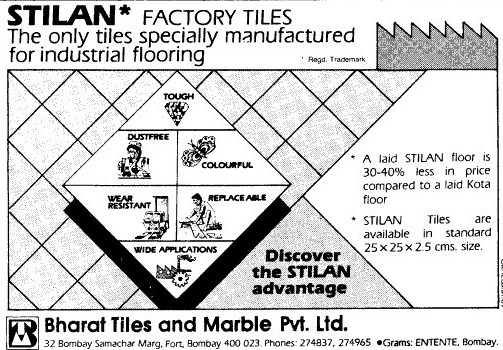

Bharat’s Stilan tiles would firmly plant them on the map of India’s burgeoning industrial landscape in the 1970s and 1980s. The business for Bharat’s mosaic tiles declined, contrasting with a rise in demand for vitrified ceramic tiles. The fast growing trend of high rise apartment complexes and buildings in urban areas necessitated the use of standardized vitrified tiles which gradually pushed out Bharat’s mosaic and patterned tiles. Never one to passively accept changes, Bharat sought out new markets by developing an industrial product. A unique, tough, abrasion resistant tile ideal for heavy use. A tile which was anti-static, making it perfect for large mechanised spaces. The Stilan tile. A proud Bharat innovation. The product was trademarked in 1960.

Fayaz Mukhtiar, C.E.O at Bharat, remembers the origins of Stilan tiles. “Stilan was a brand Bharat created. And that time they had another company – their main company Grindwell Norton. So Grindwell Norton used to manufacture those abrasion grains. The grains were one of the components of the Stilan tiles on the surface. So they used to make hard abrasion resistant tiles. And emery and the grains, we used to say they were hardest after diamonds. That is how the whole campaign was in our advertisement and brochures.”

One of Stilan’s strongest competitors was the Kota stone. The naturally available limestone was a product that was mined from Rajasthan. It was usually greenish blue and brown in color. Its durability made it a popular choice in factories and other industrial spaces. The stone was cut into smaller pieces before being laid out. Most importantly, the stone which was economical and quite readily available throughout India made it an apt choice for industrial clients before the arrival of Stilan.

Another option was to have a poured concrete floor. When done correctly, it was reinforced making it a cheap and durable flooring option for factories. The resulting floor was smooth and strong. However, the disadvantage of a concrete floor was that over time it would develop cracks.

Stilan stood firm against its competitors the Kota stone and poured reinforced concrete floors.

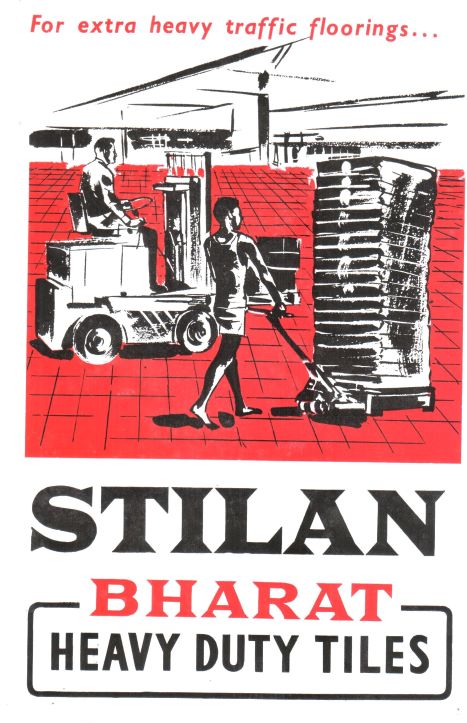

Stilan came in to cater to the demands of the industries and warehouses. Its abrasion resistant surface was its USP with an early sales brochure saying that it was next to the diamond in terms of hardness. The company went about advertising it in a clever way. Fayaz says, “Stilan was advertised aggressively. We used to have a forklift sort of thing, and used to say that a forklift can go over these tiles. Normally people didn’t have the concept that a forklift could go over a tiled floor. They used to consider it could be done only on a concrete floor or a road. So these tiles were made in that fashion. They could move around in a factory with a forklift if you put these tiles in.”

Bombay’s textile mills were the largest employers of the city in the 1960s and 1970s. Mill owners who had access to good quality cotton from nearby Gujarat, cheap electricity, funds, and an established system of labour contractors which ensured a steady supply of labour, had made fortunes through the mills. Taking advantage of the economies of scale the industry had become one of the largest in the world in the 19th century. This progress continued through the 20th century, although in the 1960s a decline had set in due to a myriad of factors including government support to handloom, the arrival of the much more efficient powerloom, poor management of mills and a rise in wage demands by workers who faced looming inflation. However, things were still running more or less smoothly and the strike that would cripple the industry in the 1980s was still far off. Mills were thriving and it was these that became the foremost users of Stilan tiles in the city then. This 10x10 tile boasted a clientele of the likes of Century Mills, Bombay Dyeing and Tata Mills. Recalling how Stilan became ‘standard’ with the Bombay mills, Fayyaz says, “That is because there are consultants who do this...so if our consultants are for X mill then Y mill also wants the same specs. Even the architects, designers especially the structural architects and the consultants. They used to have, ki this is used in a particular mill. So that is a standard thing for others also”. Different clients favored different colors of the Stilan. Century Mills installed yellow. Some had red like Bombay Dyeing and Tata Mills.

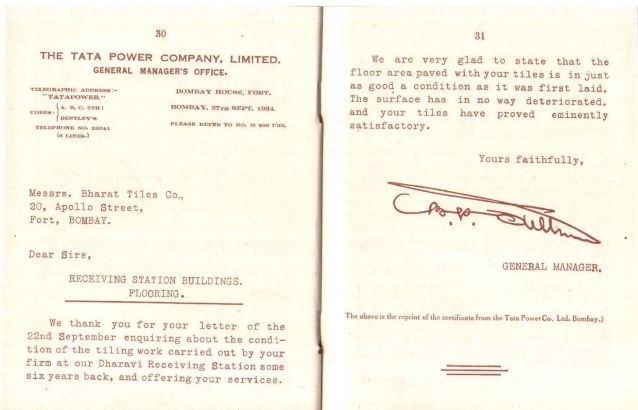

Stilan was also a popular choice with power plants. Large power stations were installed with heavy machinery which could not be upheld by ceramic floors which were considered fragile.The anti static properties of the stilan made it an attractive choice for the power plants and the small size of the tiles meant that they could be replaced easily wherever they had been damaged. The Tata Power site and its many substations as well as L&T power plants were paved with stilan tiles.

A client in Korba , Madhya Pradesh required stilan tiles in large quantities for its massive plant. Given the distance between Bombay and Korba then, it proved difficult to produce and transport the tiles all the way to M.P efficiently and economically. It was then decided that Rumi Palsekar, who had been with Bharat since the 1960s would manage a new unit that Bharat would set up in Korba, close to the client for a faster supply line of the tiles. This new unit had 2 presses operated for the duration of the project.

Stilan however, ran up against problems in the course of time. It was a low margin product that was dependent on massive volumes to ensure decent earnings from a project. At its peak the Kurla factory of Bharat employed 450 workers producing Stilan tiles. From this peak, the gradual descent of the mills in the city eroded the client base of the company. The product that needed volume to be sustainable now did not even have that. And by the 1990s Bharat had to stop the production of Stilan, realising that now it had become a loss making product.

You may also like

-

26The Ritz Hotel“Where else, but the Ritz?”, exclaimed Sudhanshu aloud, all the while quietly thinking about the two cheetahs and their owner, the cabaret dancer, in The Ritz.Read More

26The Ritz Hotel“Where else, but the Ritz?”, exclaimed Sudhanshu aloud, all the while quietly thinking about the two cheetahs and their owner, the cabaret dancer, in The Ritz.Read More -

27My Home Series: Nayana Kathpalia: Coming Back HomeA space for to grow, to take on the world but also a place to retreat and rest your weary soul - Nayana Kathpalia’s home in Swastik Court, Oval Maidan provides one example.Read More

-

28Members OnlyExplore this photo feature of all the Bharat floors adorning the corridors of the most exclusive clubs across the countryRead More

28Members OnlyExplore this photo feature of all the Bharat floors adorning the corridors of the most exclusive clubs across the countryRead More