100 Years

100 Stories

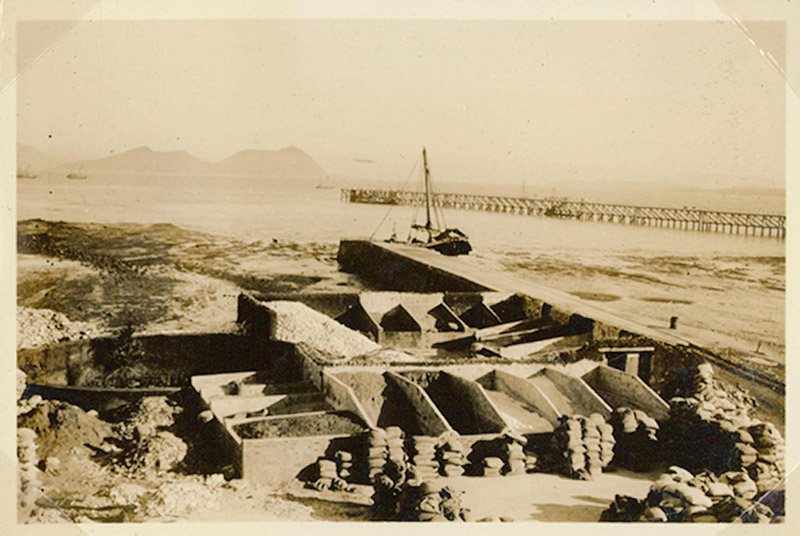

A view of the dock from the Uran factory, BFT Archives

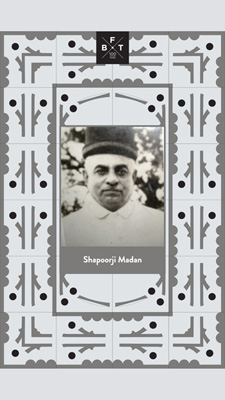

One cannot build an empire all by oneself. The founders of an empire need a vision, a plan and, most importantly, exceptionally able administrators who can execute their vision. The story of Shapoorji Madon is one such story - the story of a man who realised the vision that Pheroze and Rustom Sidhwa had during the crucial first 20 years of tile production.

The Sidhwas stumbled upon a reserved, clever and proficient Shapoorji Madon by fate. Mr. Madon had all the qualities that the Sidhwas were looking for - stern, logical, loyal and, most importantly, someone who understood the importance of high quality for the venture they were trying to embark upon. With brief initial guidance Madon absorbed the necessary knowledge and the technology the Sidhwas brought from their visits abroad. Without water or electricity or transport, on the outskirts of the fishing village of Mora, Shapoorji Madon rose to the challenges of building and running a factory to make tiles that would soon replace the imported Minton tiles from England. Madon handled the entire factory of 800 workers from the flat above the factory where he lived with his wife Shirinbai. He chose to stay where the action was, wanting nothing to escape his sharp eye. Sitting on a wooden Planter’s chair in his sadra, his black velvet prayer cap and his sapaat slippers, with his beloved hunting rifle in the corner, and between frequent pinches of snuff and sneezes, Madon would call the supervisors up to meet him for instructions. He was a tough but well loved taskmaster. who set rigorous standards of quality of work on the factory floor. As the respect he commanded went beyond the factory, he was elected President of the Uran Municipal Corporation. His name and that of Dinsha Patel, his successor, is engraved on a slab of the building he commissioned for fisherfolk and vegetable sellers to sell their produce. Rightly he was called the King of Uran.

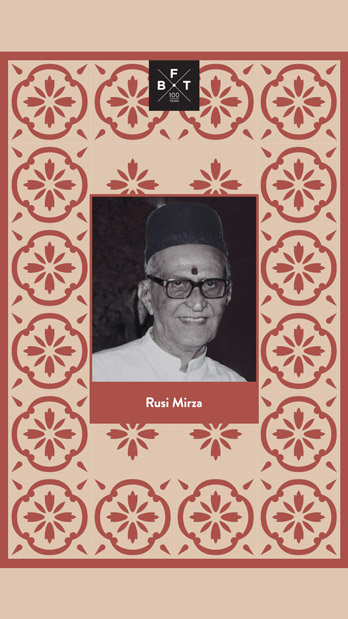

The hallmark of good leaders is in the ability to create a second tier that is as capable, or more so, than them. In the factory Shapoorji was aided by his wife’s nephew, young Dinsha Patel. Shapoorji Madon’s son in law Keki Engineer looked after maintenance, but nephew Dinsha Patel was his successor. In 1925, Dinsha had left behind his family business of a theater and a liquor store in Bardi, Gujarat and had come to the shores of Bombay searching for a job. His uncle Shapoorji saw in the bright eyed Dinsha a desire to learn something new. Being trained under the iron man himself, Dinsha was able to pick up the reins of the factory as Manager, when his mentor Shapoorji passed away. Gentle compared to Shapoorji, but continuing the tradition of attention to detail, Dinsha supervised the quality of sand and the proportion of colors used in making Bharat’s famed tiles. His wife, Khorshed, too took up a job at Bharat in the administrative department and thus, the Patel family, spent several years living first in Uran and later in the Kurla factory. They were given quarters and food was supplied from a common canteen. Dinsha’s son, Adil, recalls spending sunny days in the factory where they raced over mountains of sand and tiles, being chastised for breaking some in the process, climbed onto roofs, played hide and seek, flew kites and rode on the trollies used to carry tiles. Just like the man who guided him and trained him, Dinsha too had started creating the next generation of able administrators who would continue fructifying the founder’s vision and embedding their ideals deeper into the system. He found such faculties in a young man named Rustom Mirza, from a priestly family of Udvada. Not practising as a priest, Rusi yet embodied the priestly qualities of honesty, truthfulness, courage and compassion.

Rustom, or as he was popularly called, Rusi Mirza. put to good use his studies in mechanics from the Surat Technical Institute. He joined Bharat as a fitter on 13th Feb 1943, and on the very first day the Director Rustom Sidhwa told him that his future lay in mastering production so that he could one day become the factory manager. He was promoted eventually to Assistant Factory Manager under Dinsha Patel. Having worked his way up from the factory floor, Rusi was a warm, kind man always willing to hear out his workers. During the clashes between union workers and the management, the company always relied on Rusi’s warmth and ability to resolve all the issues with utmost consideration. In his daughter’s words, “My father followed a religion of good words, good thoughts and good deeds”. Rusi’s daughters Bakhtavar and Freni grew up along with Adil, Dinsha Patel's son, and were his companions in his factory shenanigans. Freni recalls being given lessons in self-reliance by the ever resourceful Tehmina Sidhwa who taught her how to repair the flush tank in the toilet. Rustom seth who made almost daily rounds of the factory, was served tea and biscuits from Mirza's kitchen. Patel and Mirza ran the factory together until Patel’s death in 1964, after which Mirza assumed his post. Along with Rustom and Tehmina Sidhwa, Rusi Mirza carried Bharat through one of its toughest phases, as orders dwindled and the future seemed uncertain. Ironically when he joined in 1943 the war was going on, almost no cement was available and only one press was working. He saw the ups and downs of shifting from Uran to Bombay, helping to set up the new factory at Kurla, and the booming art deco period of marble mosaic tiles, and then the downturn as quality conscious bungalow owners were replaced by quality indifferent high rise builders in the 1960s. Rusi retired in 1985, having given a lifetime’s worth of labour to the company and gained the love and respect of all, from Directors to workers, for his loyalty, hard work, fairness and honesty.

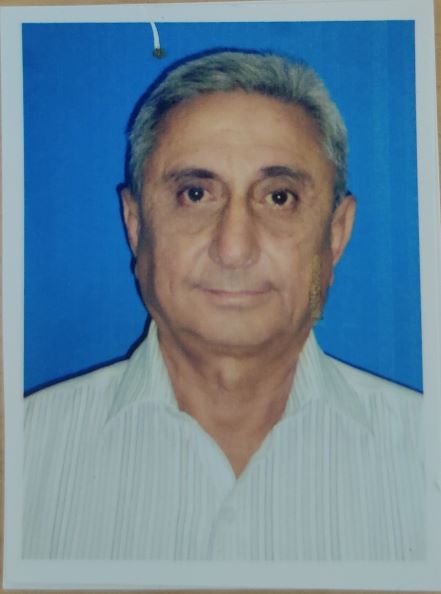

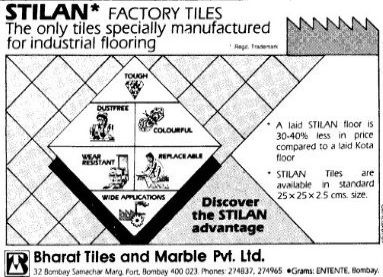

Russi was succeeded by several other factory managers, but a young boy, Rumi Palsetia, who joined Bharat at the age of 17 and was trained by Russi Mirza, became a pillar of support to Bharat. Without any formal education but with a sharp mind, courage and a desire to go up in life, Rumi had learnt the manufacture of tiles from a tough task master, Rusi Mirza. Courageous and enterprising, he and another Bharat supervisor, moonlighted as painting contractors. Rumi eventually left Bharat to set up his own contracts company, but would refuse to lay cement tiles of any other company, not sure of whether their quality would be as reliable as Bharat’s. Willing to take on any challenge, Rumi spent several years in the undeveloped area of Korba setting up and running Bharat’s first onsite tile factory for N.T.P.C’s thermal power plant and colony. In remote areas of the Tata Hydro projects, he laid the heavy duty Stilan tiles in their power houses. For 30 of the 50 years that Rumi was associated with Bharat in one capacity or another, the company faced losses and difficulties from lack of orders. Tough in talk but soft in heart, over the years he played many roles and was a support to Dilnavaz Variava when she decided to take over, rather than close down, the company’s loss making tile business by reviving the company’s original heritage range of tiles.

You may also like

-

24Standing Proud on BFT: Bharat & India’s New Financial DistrictOn the 64th foundation day of the Bombay Mutual Life Assurance Society in 1935, the oldest Insurance Institution in India fittingly celebrated the day by opening a magnificent new home - “a most striking and attractive” structure on the corner of Pherozesha Mehta and Hornby Roads in Bombay’s busy commercial district.Read More

24Standing Proud on BFT: Bharat & India’s New Financial DistrictOn the 64th foundation day of the Bombay Mutual Life Assurance Society in 1935, the oldest Insurance Institution in India fittingly celebrated the day by opening a magnificent new home - “a most striking and attractive” structure on the corner of Pherozesha Mehta and Hornby Roads in Bombay’s busy commercial district.Read More -

25Floors on which Industry thrivedBharat’s stilan tiles would firmly plant them on the map of India’s burgeoning industrial landscape in the 1970s and 1980s. The business for Bharat’s mosaic tiles declined, contrasting with a rise in demand for vitrified ceramic tiles.Read More

25Floors on which Industry thrivedBharat’s stilan tiles would firmly plant them on the map of India’s burgeoning industrial landscape in the 1970s and 1980s. The business for Bharat’s mosaic tiles declined, contrasting with a rise in demand for vitrified ceramic tiles.Read More -

26The Ritz Hotel“Where else, but the Ritz?”, exclaimed Sudhanshu aloud, all the while quietly thinking about the two cheetahs and their owner, the cabaret dancer, in The Ritz.Read More

26The Ritz Hotel“Where else, but the Ritz?”, exclaimed Sudhanshu aloud, all the while quietly thinking about the two cheetahs and their owner, the cabaret dancer, in The Ritz.Read More