100 Years

100 Stories

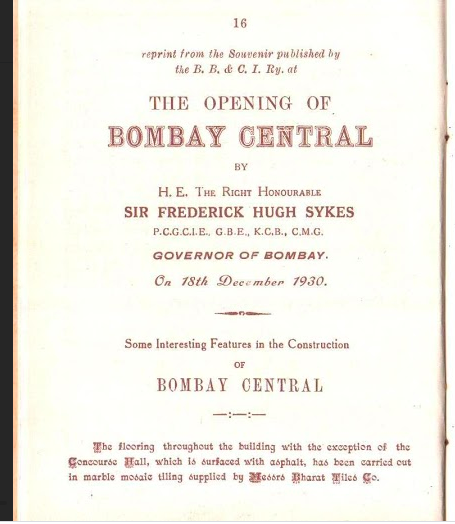

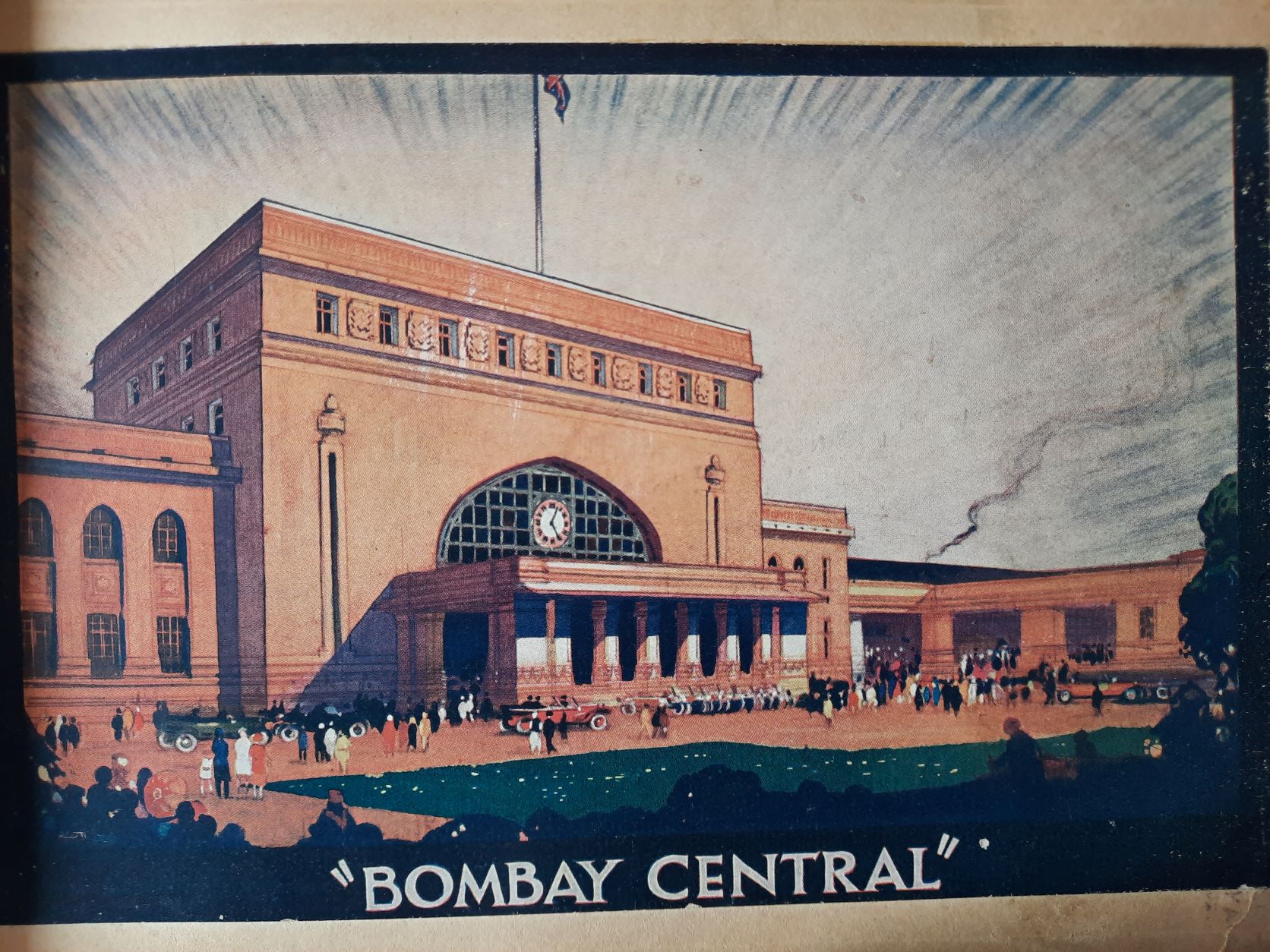

Early March 2021, while most of us were locked up in our homes as the devastating second wave reared its ugly head, a minor furrore broke out online. The facade of the 90-year old Mumbai Central Station was awashed in an eye-popping, multi-hued face-lift, leaving heritage watchers in the city aghast. After all, the restrained grandeur of this reinforced concrete structure, designed by the venerated Claude Batley, was a true product of its time. When completed in 1930, the new terminus of the Bombay-Baroda & Central India Railway (B.B.C.I) was emblematic of a bustling 20th Century metropolis upgrading its infrastructure, not only in terms of function but also by adopting a new design vocabulary which was starkly dissimilar to the colonial city’s Victorian ornamentation.

The erstwhile B.B.C.I, today known as Western Railway, was faced with a tough conundrum in the early 1920s. The Backbay Reclamation scheme, an ambitious urban development project that eventually culminated into the Marine Drive promenade, had sought urgent evacuation of the B.B.C.I’s original terminus at Colaba. Besides, the existing administrative enclave at Churchgate was proving woefully insufficient. The plan for a new terminus and an administrative headquarters was thus put on paper in 1925.

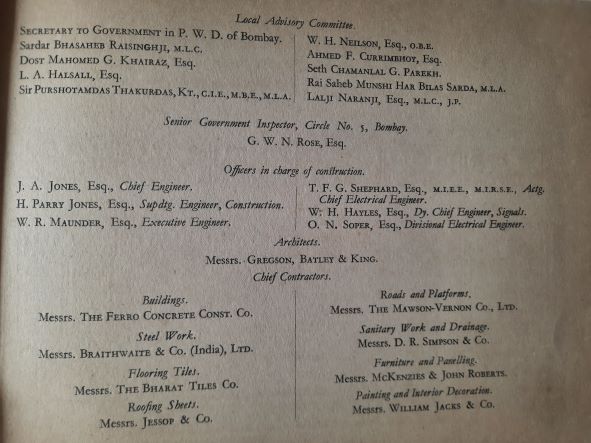

The new premises of the BBCI, designed by Batley’s architectural firm - Gregson, Batley and King, was unusual as it made a departure from the usual practice of integrating a station with the surrounding city by nestling it at a distance from the main road. The entrance quadrangle, segmented by lush green gardens - a novelty in railway architecture - led the traveller to a grand three-storied structure built in a distinctive Indian style. The portico was designed with detailing from traditional architecture and the sitting of the building was based on the Mughal style. It was built at an estimated cost of Rs 15.6 million including land, sidings, accommodation and supplementary buildings.

It was a truly modern structure made with the best available materials supplied by some of the most prominent contractors in the city. Kitchens equipped with modern enamelled gas cookers supplied by the Bombay Gas Co. Ltd, served light snack buffet spreads for first class passengers. Lifts inspired by the ones seen in London’s municipal offices, a dedicated telephone exchange, as well as holophane light fittings in the main concourse added to its contemporary appeal.

The flooring throughout the building with the exception of the concourse hall, which was surfaced with asphalt, was modern and kept in tune with a trend that was rapidly gaining followers in the 1930s. As was the case in several residential buildings that came up in Bombay during these times, particularly along Marine Drive and suburban enclaves of Dadar and Matunga, the flooring at the Bombay Central terminus was carried out in marble mosaic tiles, also known as Terrazzo tiles. Nearly the whole building, measuring about 70,000 sq. ft., was paved by Bharat’s tiles in different colours and artistic designs.

Marble mosaic tiles, especially those seen in the 1st and 2nd class waiting rooms, main hall, counters and several other important places in the building were made from high quality Italian marble chips. The in-situ dado work along the staircases and in the lounge, too, were graced with similar fine chips. Special skirting tiles in 8”x8” with channels or angles attached at the foot and non-slip staircase tiles with a finished moulded face - which did not need metal polishing - were some of the other products that Bharat supplied.

By 1930, when the Bombay Central station opened to the public, Bharat had earned a very high reputation for its tiles. The factory was equipped with modern machinery and Pheroze and Rustom Sidhwa, the uncle-nephew duo who founded the establishment, had kept abreast of the latest developments and improvements in the manufacture of various kinds of tiles. It therefore comes as no surprise that Bharat’s range of non-slip indented and checkered tiles available in grey, buff or other dark colours and typically meant for showrooms, garage porches and other heavy-traffic spaces, were also laid on platforms and ramps at the Bombay Central terminus.

Bharat started in Uran with two Italian presses but had to fight hard to conquer the common prejudice against swadeshi goods. Doubts over quality of indeginous production were rampant at the time and considerable resources were spent on learning and adapting the practices of European makers, understanding processes and sourcing raw materials required to produce tiles of the highest quality. By adapting the carpet-like designs of the encaustic Minton tiles - a hugely popular, but expensive trend at the time - to cement tiles, Bharat made luxurious flooring available to the Indian market. Over time, it earned a reputation of being pioneers in the cement tile industry with a wide variety in designs and colours. The idea of Swadeshi and self-reliance also shone through in the fact that the company went on to supply tiles and other flooring materials not just to homes but also to hardcore British establishments like the railways, the governor’houses, universities and banks.

Bharat’s superior quality products were used in the building of this terminus which was designed to withstand heavy footfall to this very day. Decades have passed, millions of shoes have grazed the surface of the tiles, and yet Bharat’s tiles have endured.

You may also like

-

19My Home: Aadya Shah: Remembering the HomeA tale about how a house can impact on one's sense of aesthetics and inspire them to create art. This is the story of Aadya and her mother Anuradha Shah in Champak, Shivaji Park, Dadar.Read More

19My Home: Aadya Shah: Remembering the HomeA tale about how a house can impact on one's sense of aesthetics and inspire them to create art. This is the story of Aadya and her mother Anuradha Shah in Champak, Shivaji Park, Dadar.Read More -

20Movie nights with BharatSpotted! Lookout for these stunning Bharat floors the next time you go for a movie! A photo feature of Bharat’s work in cinema houses and multiplexes across the country,Read More

20Movie nights with BharatSpotted! Lookout for these stunning Bharat floors the next time you go for a movie! A photo feature of Bharat’s work in cinema houses and multiplexes across the country,Read More -

21Pivot or Perish: World War II & BFTBharat faced its first major crisis, the Second World War, 17 years after it was born. Faced with cement requisitions and reduced demands, the company cleverly expanded its product range, ensuring that they would tide through a tough time.Read More

21Pivot or Perish: World War II & BFTBharat faced its first major crisis, the Second World War, 17 years after it was born. Faced with cement requisitions and reduced demands, the company cleverly expanded its product range, ensuring that they would tide through a tough time.Read More