100 Years

100 Stories

The greater the obstacle the more glory in overcoming it

March 2020. It was a month that sent industry into looming uncertainty while the world faced a viral outbreak, spiralling out of control. As people remained inside their homes, businesses grew concerned about their future prospects, wondering if they would come out safely on the other side and guessing wildly if market conditions would ever settle to pre-pandemic boom levels.

For legacy companies like Bharat Flooring Tiles, it was not the first time that its future hung in the balance due to a global crisis. Bharat had already etched its own success story, when decades earlier it skillfully navigated another seemingly insurmountable obstacle - the Second World War: the most devastating war the world had ever known, a war global in its dimension and lasting about six years long.

A European War reaches home

When Britain declared war on Nazi Germany in September 1939, India and Bharat were plunged into a production crisis neither was entirely prepared for. The British war machine in India required massive inputs from all sectors of the economy to sustain itself. Soldiers manning the frontlines had to be supplied with food, clothing, medicines and essential equipment. This had a heavy impact on Indian industry as most product supply lines were diverted to the war effort.

The war brought in draconian controls on the cement industry across distribution channels, purchase prices and quotas for open market sales. In the mayhem of war, cement was required for the construction of advanced bases, defensive lines, bunkers and military structures. Between 1939 to 1945 cement supplies were made to the Defense Services to the tune of 17 crores. By August 1942, cement companies were ordered to hand over 90% of their monthly production to the government at a fixed price. Even the remaining 10% could not be disposed of without government orders. Any requirements for civil use could be met only after the Honorary Cement Adviser or Regional Cement Advisers intervened.

The Sidhwa household was tense. Years ago, their distillery business had closed abruptly on government orders and now their tile business had closed down just as suddenly, once again on government orders. The joint family arrangement ensured that the family could survive without a stable income for some time. What bothered them, however, was the inability to pay staff.

What was Bharat to do when its primary raw material was unavailable, and the future looked just as bleak? For any other tile company the absence of a steady cement supply would have spelled the death knell. But Bharat wasn’t one to fade away so easily. Most of the diversifications in Bharat’s product line came about during the Second World War. In doing so the company demonstrated great fortitude and resourcefulness, sporting a never say die attitude.

Early Diversification

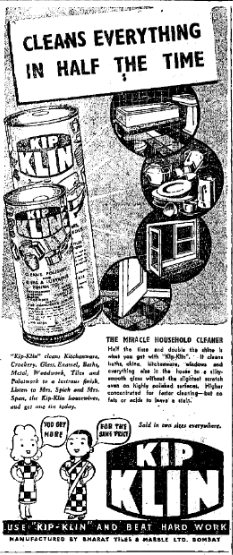

The company had already been making a cleaner, which was sold alongside tiles, and by the early 1940s, had added specialised cleaning products to its range. Handy Soap, like its name suggested, came in a bar-shaped form and could be used to clean all kinds of surfaces in the household or an industrial setting. Kip Klin seemed to be aimed more towards household use. Endorsed by its mascots, Mrs Spick and Mrs Span, Kip Klin was marketed as a one-stop, time-saving cleaner for “baths, china, kitchenware, windows and everything else in the house”

An emerging export market for Indian granite saw Mr Sidhwa set up a granite-sawing unit to slice the large blocks of granite stone and then sell the slabs onwards. Another product that came from the Bharat stable during the war years was Ariston Glue, for a “joint you can’t undo”. Deriving its name from Aristos, the Greek word for ‘best’, Ariston was a form of industrial glue, for use in factories and workshops and compatible with a range of materials, from wood to leather and glass. On the industrial side, Pheroze Sidhwa began an asbestos business which was later sold and became Hindustan Ferodo (today Hindustan Composites) and one manufacturing ‘Fluffex’ - a new age insulation material.

Bharat Metal Printers

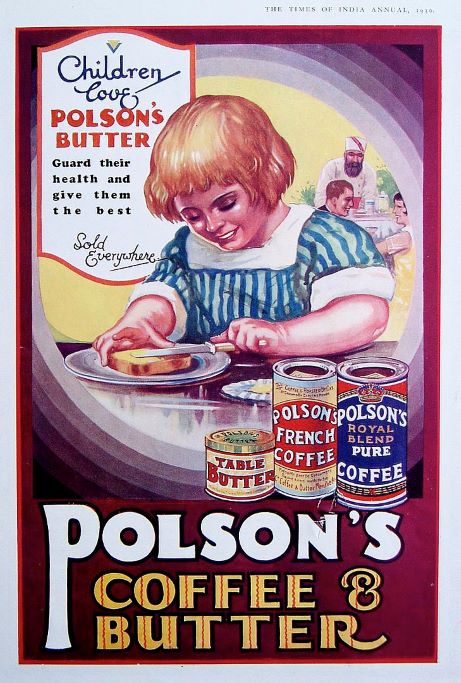

This wasn’t all. The success of Bharat Tiles had demonstrated to Rustom and Pheroze Sidhwa that swadeshi manufacturing was the need of the hour and a good product of sound quality would always win hearts. Once again, taking advantage of the land at their disposal, the uncle-nephew duo started a printing factory in Colaba, under the name Bharat Metal Printers. This concern made perfectly printed metal placards and product showcards, a ubiquitous advertising tool that played an important role in the way shops and other businesses presented their wares. The war also saw a spike in the demand for canned food and so Bharat Metal Printers forayed into manufacturing metal containers. Bharat Metal Printers supplied elaborate, colourful, artistic and long-lasting packaging for several establishments including the famous Polson’s Coffee and Butter . An article published in the Sunday Standard noted that the products of Bharat Metal Printers “are turned out to the entire satisfaction of the most exacting customers”, Bharat Metal Printers would later be sold to Metal Box India.

Grindwell Abrasives

When Pheroze Sidhwa met E.J Kaufmann-Kavan, an expert in the manufacturing of abrasive wheels, a vital tool for polishing tiles, it was as if providence was giving them an opportunity to make something great in a difficult time. Kaufmann could not return to Europe where his fellow Jews were being persecuted and instead offered to make abrasives for the Sidhwas. The first grinding wheel factory in India - Grindwell Abrasives - was thus born through the collaborative efforts of the Sidhwas, Kaufmann-Kavan and his colleague F.B Lima. Their new product was exhibited at a railway workshop where a British official presumed that it was an imported product being fraudulently sold as Indian-made! There was no better quality certificate than being mistaken for an imported product. The business gathered steam and has not looked back since. Grindwell entered into a technical collaboration with Norton Co., USA. Today it is owned by the Saint Gobain group.

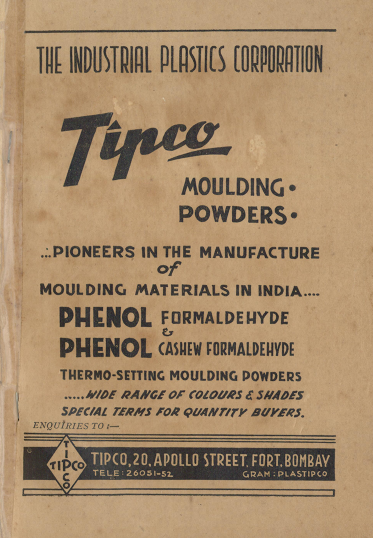

TIPCO

Another business with which the Sidhwas had ties, albeit at the gestation stage, and which went on to become a successful enterprise on its own, was TIPCO. In the early 1940s, plastic was still a novelty. It was the age of imported Bakelite and mainly seen in the market as traditional black telephones and electrical switches. The availability and imports of raw materials was making Grindwell desperate to get a steady supply of their basic raw material, i.e. Phenolic Resins or Bakelite. An Indian substitute had to be developed. Pheroze and Rustom Sidhwa approached the Royal Institute of Science, Bombay, for assistance where they met two brilliant minds - Homi Sethna and Bapulal Thakkar. Sethna, as the world knows had other plans, but Thakkar took on the challenge. Work began in a small shed on the Grindwell premises in Uran. And thus, was born Tipcolite, a local form of Bakelite. In a couple of years, Thakkar proposed to buy out the Sidhwas’ stake in the company, citing that the plastics he was working with weren’t of much use to Grindwell, which was the family’s focus at the time. TIPCO eventually grew to become a pioneer in plastics raw material and earned Mr Thakkar accolades on the national and international levels.

The war which depressed the Indian economy saw Bharat develop flexibility. The group made products that tapped into new market segments. This strategy helped keep the tile company afloat during the war years. The founders meanwhile, like all great strategists, patiently waited for the storm to pass. They were positive that the future would bring better prospects for the tile business once again. In these trying times Pheroze Sidhwa placed his future in the hands of Providence. In a diary entry he wrote, reflecting on the war years, he advises his daughters, “Change your thoughts and you change everything. We put too much dependence upon methods other than those of a spiritual nature to give us force, strength and calmness.”

And he was right. The war ended, construction began and the company went on to supply tiles to the fashionable new buildings that came up on Marine Drive. Bharat was back. And in style.

You may also like

-

22Grindwell OriginA refugee engineer, some resolve and plenty of creativity. That was all it took for the Bharat founders to launch an entirely new company in the midst of the raging Second World War, selling abrasive wheels to the British.Read More

22Grindwell OriginA refugee engineer, some resolve and plenty of creativity. That was all it took for the Bharat founders to launch an entirely new company in the midst of the raging Second World War, selling abrasive wheels to the British.Read More -

23The People Behind Bharat’s FactoriesOne cannot build an empire all by oneself. The founders of an empire need a vision, a plan and, most importantly, exceptionally able administrators who can execute their vision. The story of Shapoorji Madon is one such story - the story of a man who realised the vision that Pheroze and Rustom Sidhwa had during the crucial first 20 years of tile production.Read More

23The People Behind Bharat’s FactoriesOne cannot build an empire all by oneself. The founders of an empire need a vision, a plan and, most importantly, exceptionally able administrators who can execute their vision. The story of Shapoorji Madon is one such story - the story of a man who realised the vision that Pheroze and Rustom Sidhwa had during the crucial first 20 years of tile production.Read More -

24Standing Proud on BFT: Bharat & India’s New Financial DistrictOn the 64th foundation day of the Bombay Mutual Life Assurance Society in 1935, the oldest Insurance Institution in India fittingly celebrated the day by opening a magnificent new home - “a most striking and attractive” structure on the corner of Pherozesha Mehta and Hornby Roads in Bombay’s busy commercial district.Read More

24Standing Proud on BFT: Bharat & India’s New Financial DistrictOn the 64th foundation day of the Bombay Mutual Life Assurance Society in 1935, the oldest Insurance Institution in India fittingly celebrated the day by opening a magnificent new home - “a most striking and attractive” structure on the corner of Pherozesha Mehta and Hornby Roads in Bombay’s busy commercial district.Read More