100 Years

100 Stories

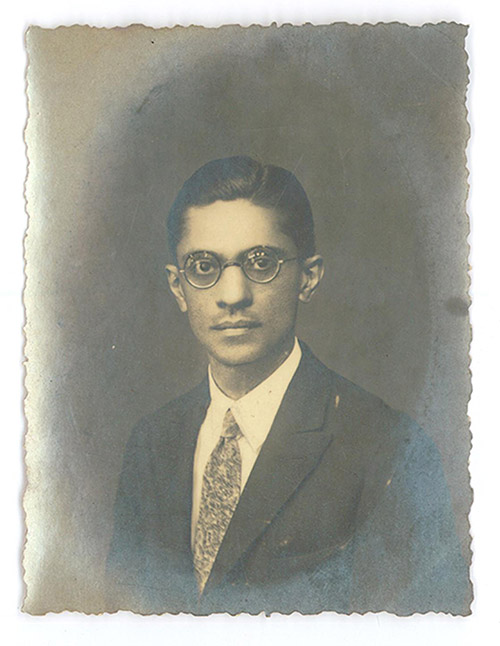

The quiet industriousness, commitment to quality and the spiritual integrity of the Bharat Flooring Tile Company’s founder set down strong roots that have enabled the company to thrive. Meet Bharat’s man for all seasons, Pheroze Sidhwa, who founded the company along with his nephew Rustom Sidhwa and his mentor Jamshed Nusserwanji Mehta

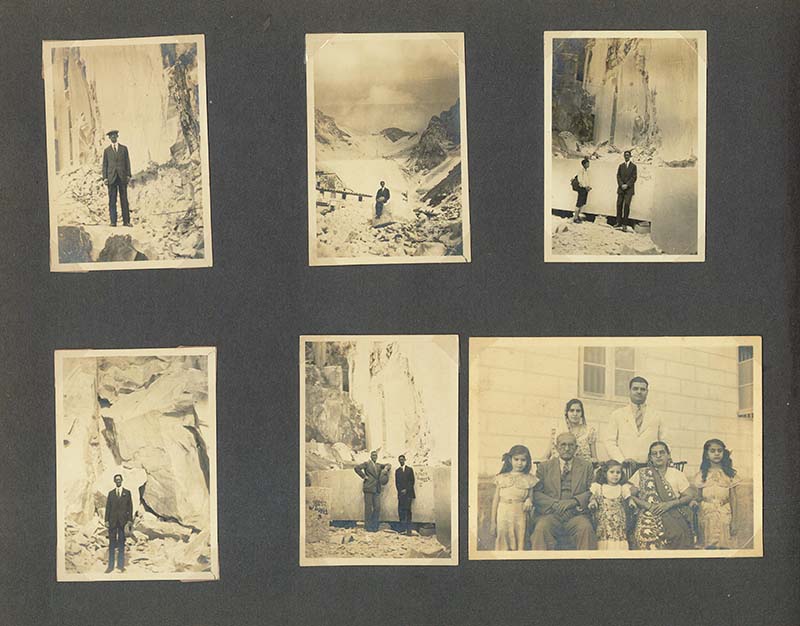

In the world of superheroes, a story of the circumstances that created these heroes can be long and complex, or identifiable by a single image or incident. If Bharat’s story were to be refined into a single image, it would be the episode where a disappointed Pherozesha Sidhwa dumped a stock of black-and-white tiles into the Arabian Sea due to his concern about their quality. He feared they would give only 25 years of service, rather than last for the lifetime of the building. Bharat was still a small company then, the loan of Rs 30,000 he had taken to start it weighed heavily on him and the Rs.57,000 value of the product that had been thus relegated to a watery demise was substantial for him. But the incident became a kind of line-in-the-sand moment for the company: Quality was never to be compromised.

It was not as though monetary value was inconsequential to Pheroze. His family had in fact seen difficult days.

THE SIDHWA FAMILY

Pheroze Sidhwa was born on 1st April, 1893 to poor parents with little or no education at Mora (Uran) in Kolaba district near Bombay. Pheroze’s father, Hormusji, worked in a distillery in Uran owned by his relatives. The distillery made liquor from roses, mahua flowers, and orange peels, but the business closed down when the British Government introduced the Bombay Abkari Act of 1878 and the Mhowra Act of 1892, limiting the manufacturing of mahua spirit and toddy to central distilleries, and applying curbs on the functioning of small distilleries.

When the distillery in Uran shut down, Hormusji Sidhwa lost his business, and within a short span, died at the age of 52. He was survived by ten children, the eldest of whom - Dhanjishah Sidhwa, supported by his wife Dinbai - then took charge of the family.

For a young Pheroze, the death of his father was the first crushing blow he faced. Pheroze penned his thoughts in a dairy as life lessons for his daughters. He remembers, “When I was only 11 years old, my father died. His death made me sad and sorry and I worried about what would happen to me. And yet there were people to take care of me. I was brought up and educated.” Dhanjishah gave up his own studies but ensured that his brothers received an education. Pheroze and Bomanshah studied law, Dinshah went on to become an architect in Karachi, Nadirshah founded Monginis and Pesi, the youngest sibling, worked with his cousins in an import export business.

Income from a few liquor shops that Dhanjisha owned took care of expenses, but Pheroze’s childhood was far from lavish. Dhanjisha’s own children and all his siblings and their families lived in a 5-storeyed house on Queen’s Road overlooking the sea, but there was rarely enough money to meet everyone’s needs. Between the young brothers, for instance, they had just two good shirts. If two of the brothers happened to go out wearing these, the others could not step out for that day! Similarly, shirts for boys were considered a luxury. Pheroze writes in his diary that he spent his time at home wearing an elder brother’s shirt which flowed down to his knees !

“Every repeated effort is a sure step to success”

When Pheroze was in Class III, he had the “distinct honour of being the last boy in the class, failing in English and Arithmetic”. That year, in Arithmetic, he got only six marks out of 100. He preferred to play rather than study, and often had to be captured and forcibly sent to school on a fisherman’s shoulders ! One year, when Pheroze was in Class 4, his older brother Dhanjisha, had had enough and insisted that Pheroze be detained in the same class. This had the desired impact and from then on little Pheroze was a changed boy “I worked very hard and soon began to keep rank among the first ten boys in class.”, he said. By the time Pheroze had reached higher classes, he held the first rank and vividly remembered the time he scored 75 marks out of 75 in Arithmetic. In his diary, he advises his daughters, “You must expect failures. But, that should on no account dishearten you, even if the failures are many. Remember, every repeated effort is a sure step to success.”

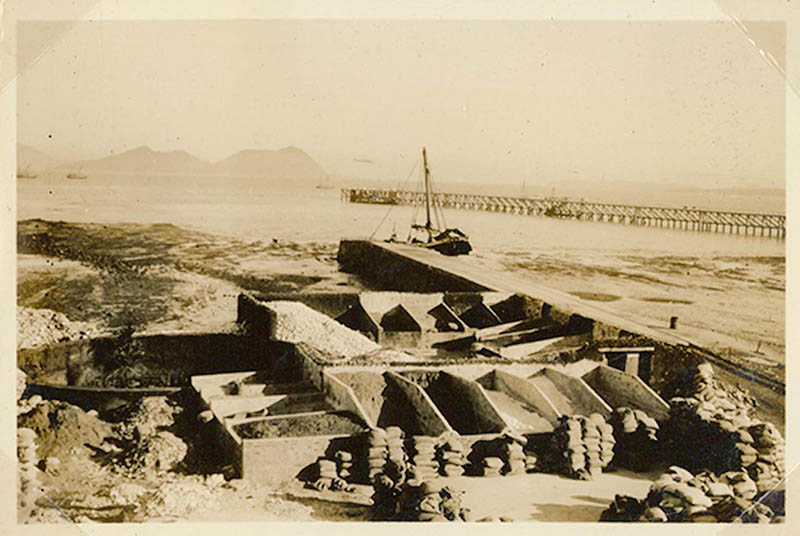

That Pheroze had to throw the tiles into the sea years later, too, did not dishearten him. He travelled to Italy with a sample of the tile and was delighted – though also dismayed – to be told that the tiles he had consigned to a watery grave were excellent in all respects except for his lack of knowledge on how to polish them ! This experience drove him to learn and improvise till he was absolutely confident of his product’s performance in Indian conditions. And soon Bharat’s superior quality cement tiles at affordable prices, nudged imported ones out of the market. With hope, courage, hard work and perseverance, Pheroze made Bharat Tiles one of the greatest successes in India. Even when the company faced its next major crisis during World War II, it was this never-say-die attitude that bailed out Bharat from extinction. In an odd and tragic echo of the distillery business, Bharat’s tile-making enterprise was also shut down, almost overnight. Steel and cement, considered crucial products were diverted for the war effort, leaving Bharat with no cement to manufacture tiles. The vast joint family provided a safety net for Pherozeshah and Rustom, but the pair also worried about the workers they were responsible for. To keep the enterprise in business as best as they could, they tried their hand at many things : producing tents for the army, pioneering printed metal containers (until a German U Boat sank their consignment of tin travelling from Africa to India), cleaning powders and tile-polishing liquid, industrial plastics, glues and abrasives. Some of the businesses were eventually sold to others, but the abrasives business went on to become an independent venture under the name of Grindwell Abrasives, now Grindwell Norton Ltd.

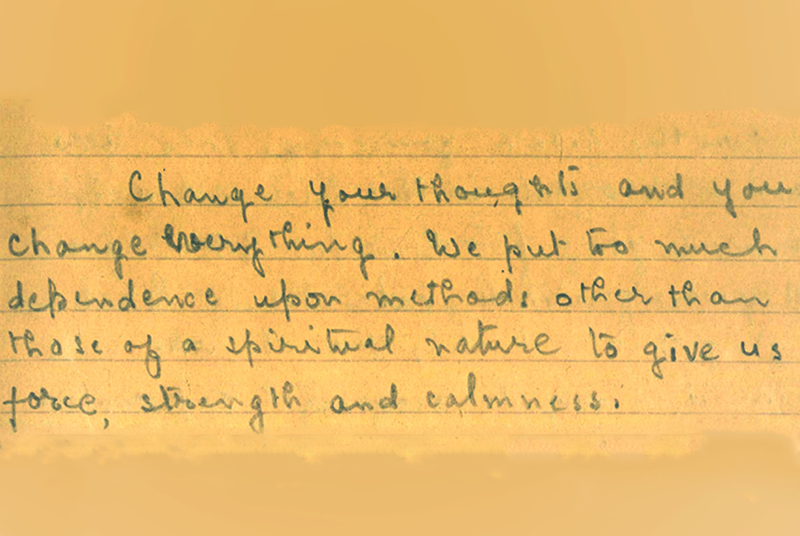

“Change your Thoughts and you Change Everything”

Even as Bharat began gaining a reputation for quality and design, and found itself supplying to landmarks like the Reserve Bank of India building and Bombay Central Station, Pheroze battled challenges on another front.

“I remember my father used to be very ill because he got cement into his lungs when he started Bharat Tiles,” Mrs Dilnavaz Variava, Pheroze’s younger daughter and Chairperson of Bharat Floorings & Tiles today, recalled. “Initially, it was wrongly diagnosed as TB. They told him he should be permanently living in a cooler and drier climate, but there was no way he could do that – his business was by the seaside!” As his condition worsened, Pheroze moved to the hill station of Deolali, near Nasik, with his wife Tehmina and daughters Almitra and Dilnavaz. For years, Pheroze alternated between the humid and hectic life in Bombay and the salubrious Deolali where he could “dry out his lungs”.

“My illness depresses me at times”, he wrote in his diary in 1949. “I should learn to take it heroically and be grateful to God that it is not worse. Never mind if the body cannot be healed, let me atleast heal myself by setting free my mind of despair and despondency.” In moments like these, Pheroze sought refuge in books such as In Tunewith the Infinite, Tagore’s Sadhana or Tolstoy’s short stories.

Over the last 100 years, Bharat has seen the world and economy change in ways that Pheroze and Rustom would have barely imagined. Periodic losses, the ebb and flow of market trends and a hostile business environment have been weathered with innovative thinking and a conscious effort to find ways of getting better at what they do. Pheroze would have been pleased to find his earliest tiles loved and retained in many buildings and his company flourishing a century later !

A Progressive Man

Pheroze’s daughters remember Pheroze as a remarkably progressive man - one who took a stand against menstrual untouchability that prevailed in the community at the time and insisted on giving his daughters the same opportunities one would give a male child.

“He made no distinction about whether you were a girl or boy. He did not want us to feel limited or intimidated and so he encouraged us to read and ask questions,” says Mrs. Dilnavaz Variava.

For the girls, evenings in Deolali were spent taking long walks with parents and reading and discussing all kinds of books including the Bhagavad Gita, the Bible and the Quran and hearing quotations from Vivekananda.

When his elder daughter Almitra’s school enrolled her into cooking and sewing classes, considered suitable for a girl, Pheroze sought an appointment with the Headmistress to ensure that Almitra would be allowed to attend science classes with the boys. Almitra ended up being the only girl in the science class. Despite having a worrying temperament he encouraged Dilnavaz to ride horses, do high altitude mountaineering and be ready to run a business. Such episodes went a long way in empowering the girls to live their lives free of societal norms. It is no wonder that Almitra went on to be the first woman to graduate from the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Dilnavaz to be one of the first two girls in its first batch of 48 students to secure an MBA at the newly established Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad.

His circumstances in life – a difficult childhood and a chronic lung condition – influenced Pherozesha’s philosophy greatly. As did his friend and mentor Jamshed Nusserwanji Mehta’s values of service to society.

In 1949, at the request of local villagers , Pheroze and Tehmina founded the Sarasvati Education Society in Deolali. The Zoroastrian Boarding High School (ZBHS) that used to run a school for Parsis had run into financial trouble, leaving several students stranded. They re-started the school with 40 students. Guided by Pheroze’s nationalistic bent, the school also threw open its doors for children from economically challenged families of all communities. Even today, the school is run by the couple’s daughters on the same principles and has grown to 3,800 children from Deolali and 20 villages around it.

Treating workers with dignity is a cornerstone of Bharat’s fundamentals. While Pheroze paid special attention to the housing, nutrition and health requirements of his workers, Rustom, Tehmina and later Dilnavaz, left no stone unturned by ensuring that their handcrafted products continued to provide livelihood, despite frequently incurring heavy losses.

In the world of business and entrepreneurship, certain events serve as life-long lessons, their values a lodestar for the company’s journey. One can say this is the case with Bharat – driven in equal parts by steadfastness and passion, by an instinct to innovate and survive, and above all to make quality, integrity, service and innovation as its guiding values. Though much has changed in the world, in the nation’s economy and in society, these values of the company that Pheroze and his partners founded 100 years ago, remain unchanged.

You may also like

-

01A Swadeshi Enterprise named BharatBharat Tiles was born in the midst of the Swadeshi movement, a child of grit and perseverance. This is Bharat’s enduring legacy.Read More

01A Swadeshi Enterprise named BharatBharat Tiles was born in the midst of the Swadeshi movement, a child of grit and perseverance. This is Bharat’s enduring legacy.Read More -

03Rustom Sidhwa: You Can’t Run A Business If You Can’t Run With ItBharat’s founder Rustom Sidhwa was an eclectic soul. Often found experimenting with cement mixtures on the weekends. Know more about the man who could solve any problem, sometimes with an ice cream, sometimes with a nugget of advice.Read More

03Rustom Sidhwa: You Can’t Run A Business If You Can’t Run With ItBharat’s founder Rustom Sidhwa was an eclectic soul. Often found experimenting with cement mixtures on the weekends. Know more about the man who could solve any problem, sometimes with an ice cream, sometimes with a nugget of advice.Read More -

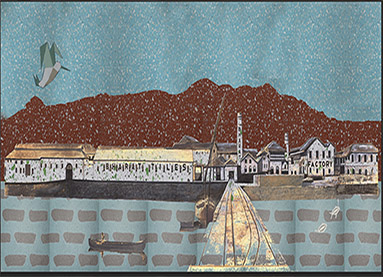

04"The Country's largest and most efficient power factory"The site of hundreds of creative experiments, installed with the top of the line equipment imported from faraway Europe. Bharat's Uran factory was where it all began.Read More

04"The Country's largest and most efficient power factory"The site of hundreds of creative experiments, installed with the top of the line equipment imported from faraway Europe. Bharat's Uran factory was where it all began.Read More